Hip Dysplasia

Diagnosis - Treatment - Prevention

Veterinary & Aquatic Services Department, Drs. Foster & Smith, Inc.

Canine hip dysplasia is a very common degenerative joint disease seen in dogs. There are many misconceptions surrounding it. There are many things that we know about hip dysplasia in dogs, there are also many things we suspect about this common cause of limping, and there are some things that we just do not know about the disease. We will cover all of those here and hope to separate out fact, theory, hypothesis, and opinion.

What is hip dysplasia?

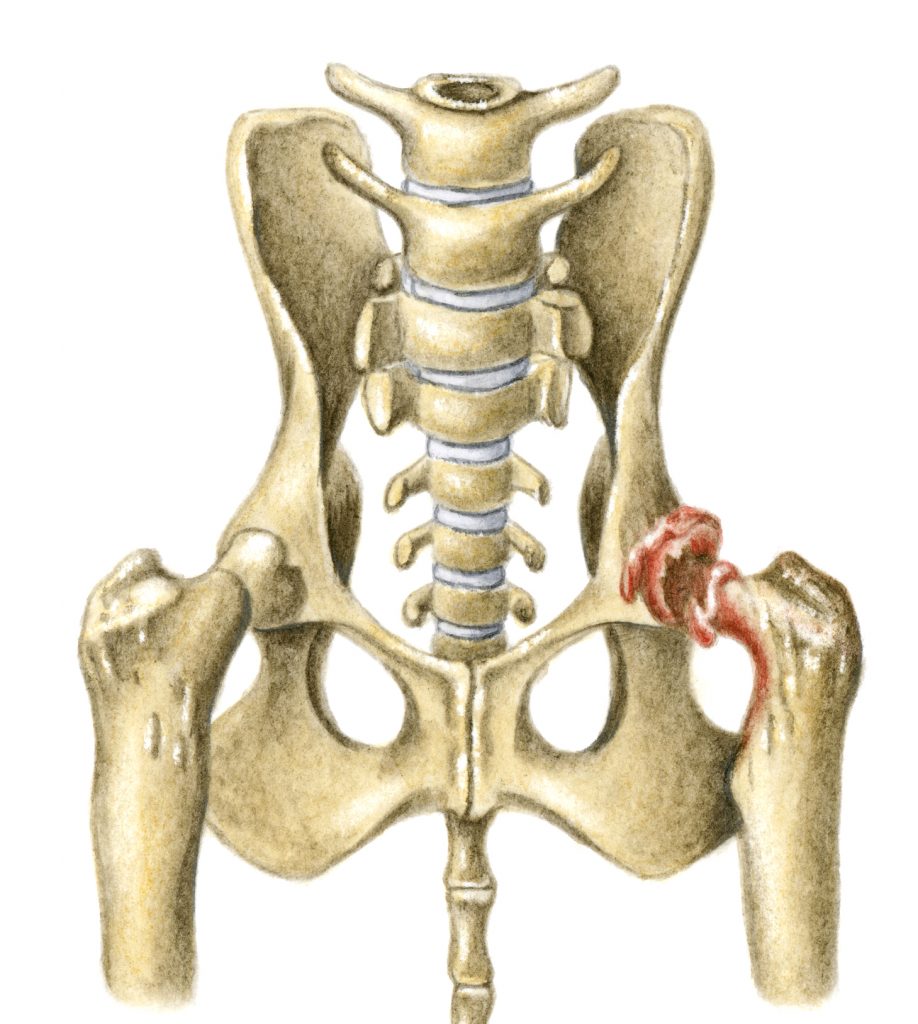

To understand what hip dysplasia really is we must have a basic understanding of the joint that is being affected. The hip joint forms the attachment of the hind leg to the body and is a ball and socket joint. The ball portion is the head of the femur while the socket (acetabulum) is located on the pelvis. In a normal joint the ball rotates freely within the socket. To facilitate movement the bones are shaped to perfectly match each other, with the socket surrounding the ball. To strengthen the joint, the two bones are held together by a ligament. The ligament attaches the femoral head directly to the acetabulum. Also, the joint capsule, which is a very strong band of connective tissue, encircles the two bones adding further stability. The area where the bones actually touch each other is called the articular surface. It is perfectly smooth and cushioned with a layer of spongy cartilage. In the normal dog, all of these factors work together to cause the joint to function smoothly and with stability.

To understand what hip dysplasia really is we must have a basic understanding of the joint that is being affected. The hip joint forms the attachment of the hind leg to the body and is a ball and socket joint. The ball portion is the head of the femur while the socket (acetabulum) is located on the pelvis. In a normal joint the ball rotates freely within the socket. To facilitate movement the bones are shaped to perfectly match each other, with the socket surrounding the ball. To strengthen the joint, the two bones are held together by a ligament. The ligament attaches the femoral head directly to the acetabulum. Also, the joint capsule, which is a very strong band of connective tissue, encircles the two bones adding further stability. The area where the bones actually touch each other is called the articular surface. It is perfectly smooth and cushioned with a layer of spongy cartilage. In the normal dog, all of these factors work together to cause the joint to function smoothly and with stability.

Hip dysplasia results from the abnormal development of the hip joint in the young dog. It may or may not be bilateral, affecting both right and left sides. It is brought about by the laxity of the muscles, connective tissue, and ligaments that should support the joint. Most dysplastic dogs are born with normal hips but due to genetic and possibly other factors, the soft tissues that surround the joint start to develop abnormally as the puppy grows. The most important part of these changes is that the bones are not held in place but actually move apart. The joint capsule and the ligament between the two bones stretch, adding further instability to the joint. As this happens, the articular surfaces of the two bones lose contact with each other. This separation of the two bones within a joint is called subluxation and this, and this alone, causes all of the resulting problems we associate with the disease.

Hip dysplasia results from the abnormal development of the hip joint in the young dog. It may or may not be bilateral, affecting both right and left sides. It is brought about by the laxity of the muscles, connective tissue, and ligaments that should support the joint. Most dysplastic dogs are born with normal hips but due to genetic and possibly other factors, the soft tissues that surround the joint start to develop abnormally as the puppy grows. The most important part of these changes is that the bones are not held in place but actually move apart. The joint capsule and the ligament between the two bones stretch, adding further instability to the joint. As this happens, the articular surfaces of the two bones lose contact with each other. This separation of the two bones within a joint is called subluxation and this, and this alone, causes all of the resulting problems we associate with the disease.

What are the symptoms of hip dysplasia?

Dogs of all ages are subject to the symptoms of hip dysplasia and the resultant osteoarthritis. In severe cases, puppies as young as five months will begin to show pain and discomfort during and after vigorous exercise. The condition will worsen until even normal daily activities are painful. Without intervention, these dogs may be unable to walk at all by a couple years of age. In most cases, however, the symptoms do not begin to show until the middle or later years in the dog's life.

The symptoms are typical for those seen with other causes of osteoarthritis. Dogs may walk or run with an altered gait, often resisting movements that require full extension or flexion of the rear legs. Many times, they run with a 'bunny hopping' gait. They will show stiffness and pain in the rear legs after exercise or first thing in the morning. Most dogs will warm up out of the muscle stiffness with movement and exercise. Some dogs will limp and many will decrease their level of activity. As the condition progresses, the dogs will lose muscle tone and may even need assistance in getting up. Many owners attribute the changes to normal aging but after treatment is initiated, they are shocked to see much more normal and pain-free movement return.

Who gets hip dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia can be found in dogs, cats, and humans, but for this article we are concentrating only on dogs. In dogs, it is primarily a disease of large and giant breeds. The disease can occur in medium-sized breeds and rarely even in small breeds. It is primarily a disease of purebreds although it can happen in mixed breeds, particularly if it is a cross of two dogs that are prone to developing the disease. German Shepherds, Labrador Retrievers, Rottweilers, Great Danes, Golden Retrievers, and Saint Bernards appear to have a higher incidence, however, these are all very popular breeds and may be over represented because of their popularity. On the other hand, Greyhounds and Borzois have a very low incidence of the disease.

What are the risk factors for the development of hip dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia is caused by looseness in the hip joint. The looseness creates abnormal wear and erosion of the joint and as a result pain and arthritis develops. The disease process is fairly straightforward; the controversy starts when we try to determine what predisposes animals to contract the disease. Almost all researchers agree that there is a genetic link involved. If a parent has hip dysplasia, then the offspring are at greater risk for developing hip dysplasia. Some researchers feel that genetics are the only factor involved, where others feel that genetics contribute less than 25% to the development of the disease. The truth probably lies in the middle. If there are no carriers of hip dysplasia in a dog's lineage, then it will not contract the disease. If there are genetic carriers, then it may contract the disease. We can greatly reduce the incidence of hip dysplasia through selective breeding. We can also increase the incidence through selectively breeding. We cannot, however, completely reproduce the disease through selective breeding. In other words, if you breed two dysplastic dogs, the offspring are much more likely to develop the disease but will not all have the same level of symptoms or even necessarily show any symptoms. The offspring from these dogs will, however, be carriers and the disease may show up in their offspring in later generations. This is why it can be difficult to eradicate the disease from a breed or specific line.

Hip dysplasia is caused by looseness in the hip joint. The looseness creates abnormal wear and erosion of the joint and as a result pain and arthritis develops. The disease process is fairly straightforward; the controversy starts when we try to determine what predisposes animals to contract the disease. Almost all researchers agree that there is a genetic link involved. If a parent has hip dysplasia, then the offspring are at greater risk for developing hip dysplasia. Some researchers feel that genetics are the only factor involved, where others feel that genetics contribute less than 25% to the development of the disease. The truth probably lies in the middle. If there are no carriers of hip dysplasia in a dog's lineage, then it will not contract the disease. If there are genetic carriers, then it may contract the disease. We can greatly reduce the incidence of hip dysplasia through selective breeding. We can also increase the incidence through selectively breeding. We cannot, however, completely reproduce the disease through selective breeding. In other words, if you breed two dysplastic dogs, the offspring are much more likely to develop the disease but will not all have the same level of symptoms or even necessarily show any symptoms. The offspring from these dogs will, however, be carriers and the disease may show up in their offspring in later generations. This is why it can be difficult to eradicate the disease from a breed or specific line.

Nutrition: Experimentally, we can increase the severity of the disease in genetically susceptible animals in a number of ways. One of them is through obesity. It stands to reason that carrying around extra weight will exacerbate degeneration of the joint in a dog with a loose hip. Overweight dogs are therefore at a much higher risk. Another factor that may increase the incidence is rapid growth in a puppy during the ages from three to ten months. Experimentally, the incidence has been increased in genetically susceptible dogs when they are given free choice high protein and high calorie diets. In a large study done in 1997, Labrador Retriever puppies fed a high protein, high calorie diet free choice for three years had a much higher incidence of hip dysplasia than their littermates who were fed the same high calorie, high protein diet but in an amount that was 25% less than that fed to the dysplastic group. As might be expected, however, the free choice group was significantly heavier at maturity and averaged 22 pounds heavier than the control group. Because obesity is also a risk factor, this study may be difficult to interpret.

We have yet to see a study that links an increased incidence of hip dysplasia in dogs fed a normal diet of commercial puppy food versus a specialty diet formulated for just large breed dogs.

There have also been studies looking into protein and calcium levels and their relationship to hip dysplasia. Both of these studies were able to increase the level of hip dysplasia by feeding increased amounts of calcium and protein. But once again, the studies of puppies fed greatly increased amounts over normal recommended values and compared them to animals fed decreased amounts. They failed to compare puppies fed a normal amount of food that had the recommended amount of protein, fat, and calcium to those fed a diet with slightly less protein, fat, and calcium (similar to those 'large breed puppy foods' that are now flooding the market). We have yet to see a study that links an increased incidence in hip dysplasia in dogs fed a normal diet of commercial puppy food versus a specialty diet formulated just for large breed puppies.

Exercise: Exercise may be another risk factor. It appears that dogs that are genetically susceptible to the disease may have an increased incidence of disease if they over-exercised at a young age. But at the same time, we know that dogs with large and prominent leg muscle mass are less likely to contract the disease than dogs with small muscle mass. So exercising and maintaining good muscle mass may actually decrease the incidence of the disease. Moderate exercise that strengthens the gluteal muscles, such as running and swimming, is probably a good idea. Whereas, activities that apply a lot of force to the joint are contraindicated. An example would be jumping activities such as playing Frisbee.

How is hip dysplasia diagnosed?

Diagnosis of hip dysplasia in dogs that are showing clinical signs of arthritis and pain is usually made through the combination of a physical exam and radiographs (x-rays). If a dog is showing outward signs of arthritis, there are usually easily recognized changes in the joint that can be seen on radiographs. In addition, the veterinarian may even be able to feel looseness in the joint or may be able to elicit pain through extension and flexion. Regardless, the results are straightforward and usually not difficult to interpret.

However, about half of the animals that come in for a determination on the health of their hip joints are not showing physical signs, but are intended to be used for breeding. The breeder wants to ensure that the animal is not at great risk for transmitting the disease to his or her offspring. There are two different testing methods that can be performed. The traditional and still most common is OFA testing. The other newer technique is the PennHip method.

OFA: The method used by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) has been the standard for many years. The OFA was established in 1966, and has become the world's largest all-breed registry. The OFA maintains a database of hip evaluations for more than 475,000 dogs. Radiographs are taken by a local veterinarian under specific guidelines and are then submitted to the OFA for evaluation of hip dysplasia and certification of hip status. Since the accuracy of radiological diagnosis of hip dysplasia using the OFA technique increases after 24 months of age, the OFA requires that the dog be at least two years of age at the time the radiographs are taken. They also recommend that the evaluation should not be performed while the female is in heat. To get the correct presentation and ensure that the muscles are relaxed, the OFA recommends that the dog be anesthetized for the radiographs. OFA radiologists evaluate the hip joints for congruity, subluxation, the condition of the acetabular margins and acetabular notch, and the size, shape, and architecture of the femoral head and neck. The radiographs are reviewed by three radiologists and a consensus score is assigned based on the animal's hip conformation relative to other individuals of the same breed and age. Using a seven point scoring system, hips are scored as normal (excellent, good, fair), borderline dysplastic, or dysplastic (mild, moderate, severe). Dogs with hips scored as borderline or dysplastic are not eligible to receive OFA breeding numbers.

When dogs born in 1972 to 1980 were compared with dogs born in 1989 and 1990, 60% of the breeds demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in hip dysplasia. At the same time, 68% of breeds had a statistically significant increase in the number of hips scored as excellent.

The OFA will also provide preliminary evaluations (performed by one OFA radiologist) of dogs younger than 24 months of age to help breeders choose breeding stock. Reliability of the preliminary evaluation is between 70 and 100% depending on the breed. Results published by the OFA suggest that the incidence of hip dysplasia in certain breeds has decreased as a result of selective breeding programs. When dogs born in 1972 to 1980 were compared with dogs born in 1989 and 1990, 60% of the breeds demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in hip dysplasia. At the same time, 68% of breeds had a statistically significant increase in the number of hips scored as excellent. This information may suggest progress is being made to decrease the frequency of hip dysplasia, but it may simply be that only radiographs from dogs thought to have normal hips are being submitted to the OFA, while those with dysplasia are being screened out by referring veterinarians.

PennHIP: The diagnostic method used by the University of Pennsylvania Hip Improvement Program (PennHIP) uses distraction/compression radiographic views to more accurately identify and quantify joint laxity. Radiographs of the hip joints are taken with the dog under heavy sedation. Two views are obtained with the hind limbs in neutral position to maximize joint laxity. Weights and an external device are used to help push the head of the femur further into or away from the acetabulum. The amount of femoral head displacement (joint laxity) is quantified using a distraction index (DI). The DI ranges from 0 to 1 and is calculated by measuring the distance the center of the femoral head moves laterally from the center of the acetabulum and dividing it by the radius of the femoral head. A DI of 0 indicates a very tight joint. A DI of 1 indicates complete luxation with little or no coverage of the femoral head. A hip with a distraction index of .6 is 60% luxated and is twice as lax as a hip with a DI of .3. When the DI was compared to the OFA scores for 65 dogs, all dogs scored as mildly, moderately, or severely dysplastic by the OFA method had a DI above .3.

Hip joint laxity as measured by the DI is strongly correlated with the future development of osteoarthritis. Hips with a low DI are less likely to develop osteoarthritis. Hips with a DI below .3 rarely develop osteoarthritis visible on radiographs. Although hips with a DI above .3 are considered "degenerative joint disease susceptible" not all hips with a DI greater than .3 eventually develop osteoarthritis. It is known that some hips with radiographically apparent laxity do not develop osteoarthritis. A means of differentiating lax hips that develop osteoarthritis from those that will not is important in developing a prognosis and making treatment recommendations. In one study, the DI obtained from dogs at four months of age was a good predictor of later osteoarthritis, though the 6 and 12-month indices were more accurate.

To assure quality and repeatability among diagnostic centers using the PennHip technique, veterinarians must take a special training course to become certified. As this technique gains popularity more and more veterinarians are becoming certified.

How is hip dysplasia treated surgically?

There are several surgical procedures available depending on the age and the severity of the joint degeneration.

Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO): TPO is a procedure used in young dogs usually less than 10 months of age that have radiographs that show severe hip laxity, but have not developed severe damage to the joints. The procedure involves a surgical breaking of the pelvic bones and a realignment of the femoral head and acetabulum restoring the coxofemoral weight-bearing surface area and correcting femoral head subluxation. This is a major surgery and is very expensive, but the surgery has been very successful on animals that meet the requirements.

Total Hip Replacement: may be the best surgical option for dogs that have degenerative joint disease as a result of chronic hip dysplasia. Total hip replacement is a salvage procedure that can produce a functionally normal joint, eliminate degenerative changes, and alleviate joint pain. The procedure involves the removal of the existing joint and replacing it with a prosthesis. To be a candidate for this procedure, the animal must be skeletally mature and is usually performed on dogs weighing at least 20 pounds. There is no maximum size limit. If both hips need to be replaced, there is a three-month period of rest recommended between the surgeries. As with the TPO surgery, this is a very expensive procedure but has had some very good results.

Femoral Head and Neck Excision: Femoral head and neck excision is a procedure in which the head of the femur is surgically removed and a fibrous pseudo-joint forms. This procedure is considered a salvage procedure and is used in cases where degenerative joint disease has occurred and total hip replacement is not feasible. The resulting pseudo-joint will be free from pain and allow the animal to increase its activity, however, full range of motion and joint stability are decreased. For best results, the patient should weigh less than 45 pounds, however, the procedure may be performed on larger dogs.

Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis: A new, less invasive surgery for treating hip dysplasia, called Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis, is currently being evaluated. This surgery prematurely fuses two pelvic bones together, allowing the other pelvic bones to develop normally. This changes the angle of the hips, lessening the likelihood of arthritis. Early diagnosis is critical, since the procedure must be done before 20 weeks of age, preferably 16 weeks.

Pectineal Myectomy: This is a somewhat controversial treatment for patients with chronic hip dysplasia. The pectineus is one of the muscles attaching the femur to the pelvis. By cutting and removing this muscle, the tension on the joint and joint capsule are reduced. This offers some pain relief for some patients, but does not slow the progression of the disease. There are possible complications with this procedure and with the introduction of the newer, better procedures. This surgery is rarely performed anymore.

How is hip dysplasia treated medically?

Because hip dysplasia is primarily an inherited condition, there are no products on the market that prevent the development of hip dysplasia.

Because hip dysplasia is primarily an inherited condition, there are no products on the market that prevent the development of hip dysplasia.

Medical treatment of hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis has greatly improved in the last several years thanks to the introduction and approval of several new supplements and drugs. Because hip dysplasia (and other types of dysplasias) are primarily inherited conditions, there are no products on the market that prevent their development. Through proper diet, exercise, supplements, anti-inflammatories, and pain relief, you may be able to decrease the progression of degenerative joint disease, but the looseness in the joint or bony changes will not change significantly.

Medical management is indicated for both young dogs with clinical signs and for older dogs with chronic osteoarthritis. Because of the high cost involved with many surgeries, medical management is many times the only realistic option for many pet owners. Medical management is multifaceted. For the best results, several of the following modalities should be instituted. For most animals, veterinarians begin with the first recommendations and work their way down this list as needed to control the pain and inflammation associated with degenerative joint disease.

Weight Management

Weight management is the first thing that must be addressed. All surgical and medical procedures will be more beneficial if the animal is not overweight. Considering that up to half of the pets in the U.S. are overweight, there is a fair chance that many of the dogs with hip dysplasia/osteoarthritis are also overweight. Helping a dog lose pounds until he reaches his recommended weight, and keeping it there, may be the most important thing an owner can do for a pet. However, this may be the hardest part of the treatment, but it is worth it. You, as the owner, have control over what your dog eats. If you feed an appropriate food at an appropriate level and keep treats to a minimum, your dog will lose weight.

Exercise

Exercise is the next important step. Exercise that provides for good range of motion and muscle building and limits wear and tear on the joints is the best. Leash walking, swimming, walking on treadmills, slow jogging, and going up and down stairs are excellent low-impact exercises. An exercise program should be individualized for each dog based on the severity of the osteoarthritis, weight, and condition of the dog. In general, too little exercise can be more detrimental than too much, however the wrong type of exercise can cause harm. While watching a dog play Frisbee is very enjoyable and fun for the dog, it is very hard on a dog's joints. Remember, it is important to exercise daily; only exercising on weekends, for instance, may cause more harm than good if the animal is sore for the rest of the week and reluctant to move at all. Warming the muscles prior to exercise and following exercise with a "warm-down" period are beneficial. Consult with your veterinarian regarding an exercise program appropriate for your dog.

Warmth and good sleeping areas

Most people with arthritis find that the signs tend to worsen in cold, damp weather. Keeping your pet warm, may help him be more comfortable. A pet sweater will help keep joints warmer. You may want to consider keeping the temperature in your home a little warmer, too.

Providing a firm, orthopedic foam bed helps many dogs with arthritis. Beds with dome-shaped, orthopedic foam distribute weight evenly and reduce pressure on joints. They are also much easier for the pet to get out of. Place the bed in a warm spot away from drafts.

Massage and physical therapy

Your veterinarian or the veterinary staff can show you how to perform physical therapy and massage on your dog to help relax stiff muscles and promote a good range of motion in the joints. Remember, your dog is in pain, so start slowly and build trust. Start by petting the area and work up to gently kneading the muscles around the joint with your fingertips using a small, circular motion. Gradually work your way out to the surrounding muscles. Moist heat is also beneficial.

Making daily activities less painful

Going up and down stairs is often difficult for arthritic pets, and for dogs, it can make going  outside to urinate and defecate very difficult. Many people build or buy ramps, especially on stairs leading to the outside, to make it easier for the dogs to go outside.

outside to urinate and defecate very difficult. Many people build or buy ramps, especially on stairs leading to the outside, to make it easier for the dogs to go outside.

Larger breed dogs can especially benefit from elevating their food and water bowls. Elevated feeders make eating and drinking more comfortable for arthritic pets, particularly if there is stiffness in the neck or back.

Oral Disease-Modifying Osteoarthritis Agents

Glucosamine and Chondroitin: Glucosamine and Chondroitin are two ingredients of supplements that have become widely used in treating both animals and humans for osteoarthritis. Due to the overwhelming success in treating patients with osteoarthritis, these products have come to the forefront of therapy and are becoming the most popular products for managing arthritis today.

Glucosamine is the major sugar found in glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronate, which are important building blocks in the synthesis and maintenance of cartilage in the joint. Chondroitin enhances the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and inhibits damaging enzymes in the joint.

When a dog has hip dysplasia or other osteoarthritis, the joint wears abnormally and the protective cartilage on the surface of the joint gets worn away and the resultant bone-to-bone contact creates pain. Glucosamine and chondroitin give the cartilage-forming cells (chondrocytes) the building blocks they need to synthesize new cartilage and to repair the existing damaged cartilage. These products are not painkillers; they work by actually healing the damage that has been done. These products generally take at least six weeks to begin to heal the cartilage and most animals need to be maintained on these products the rest of their lives to prevent further cartilage breakdown. These products are very safe and show very few side effects. There are many different glucosamine/chondroitin products on the market, but they are not all created equal. We have seen the best results from products that contain pure ingredients that are human grade in quality. Products such as Drs. Foster and Smith Joint Care and Gluco-C, or the veterinary-sold product Cosequin are several that fit this category.

S-Adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe, Denosyl SD4): A recent product, Denosyl SD4, has been advocated for the management of osteoarthritis in people. The efficacy of this product for the management of osteoarthritis in animals has not been fully determined, however it is being used as a treatment for liver disease in dogs and cats. It has both anti-inflammatory and pain relieving properties.

Perna Mussels: Perna canaliculus, or green-lipped mussel, is an edible shellfish found off the shores of New Zealand. The soft tissue is separated from the shell, washed several times, frozen, and freeze-dried. It is then processed into a fine powder and added to products. It is made up of 61% protein, 13% carbohydrates, 12% glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), 5% lipids (including eicosatetraenoic acids, or ETAs), 5% minerals, and 4% water. It also contains glucosamine, a GAG precursor and one of the building blocks of cartilage. Glucosamine, GAGs (unbranched chains of complex sugars) and ETAs (a type of Omega-3 fatty acids) are the compounds in the mussel believed to contribute to its beneficial effects. ETAs are the key ingredients that help in the anti-inflammatory activity and thereby the reduction of joint pain. GAGs are the main components of cartilage and the synovial fluid found in joints.

Tetracyclines: Some tetracyclines such as doxycycline and minocycline have been shown to inhibit enzymes that break down cartilage. The results of one research study suggested that doxycycline reduced the degeneration of cartilage in dogs with ruptured cruciate ligaments. Further studies need to be done to evaluate the benefit of these tetracyclines in the treatment of osteoarthritis in dogs.

Injectable Disease-Modifying Osteoarthritis Agents

Polysulfated Glycosaminoglycan (Adequan): Adequan is a product that is administered as an injection. A series of shots are given over weeks and very often have favorable results. The cost and the inconvenience of weekly injections are a deterrent to some owners, especially since the oral glucosamine products are so effective. This product helps prevent the breakdown of cartilage and may help with the synthesis of new cartilage. The complete mechanism of action of this product is not completely understood, but appears to work on several different areas in cartilage protection and synthesis.

Hyaluronic Acid (Legend): Hyaluronic acid is an important component of joint fluid. Including it in the management of osteoarthritis may protect the joint by increasing the viscosity of the joint fluid, reducing inflammation and scavenging free radicals. Most of the research on hyaluronic acid has been done in people and horses, but it may also be effective in dogs. This is an injectable product which is administered directly into the joint.

Other Oral Supplements

Methyl-sulfonyl-methane (MSM): MSM is a natural, sulfur-containing compound produced by kelp in the ocean. MSM is reported to enhance the structural integrity of connective tissue, and help reduce scar tissue by altering cross-linkages which contribute to scar formation. MSM has been promoted as having powerful anti-inflammatory and pain reducing properties.

Creatine: Creatine is an amino acid derivative formed in the liver, kidneys, and pancreas from the amino acids arginine, glycine, and methionine. It is found in red meat and fish. Creatine is not a muscle builder, but aids in the body production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a fuel, for short, intense bursts of energy. In humans, it builds lean body mass by helping the muscle work longer, allowing one to train harder, lift more weight, and have more repetitions. It is the increase in exercise which results in building muscle, not creatine alone. Creatine may be helpful in dogs with muscle atrophy associated with osteoarthritis.

Vitamin C: Vitamin C acts as an antioxidant and is an important nutrient in the synthesis of collagen and cartilage. Because dogs and cats can manufacture their own Vitamin C and do not require it in their diet like humans do, the efficacy of using Vitamin C in the management of osteoarthritis in dogs remains unclear. Supplementing with Vitamin C at a reasonable level will not result in a toxicity and may prove to have a beneficial effect.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Omega-3 fatty acids are often used for the management of the signs of atopy in dogs. Because of their anti-inflammatory properties, some have advocated their use in dogs with osteoarthritis. Research studies are under way to determine their effectiveness in the management of osteoarthritis.

Duralactin: Recently, a patented ingredient obtained from the milk of grass-fed cows has been studied and marketed for the management of musculoskeletal disorders in dogs. It is called Duralactin, has anti-inflammatory properties, and is a non-prescription product. It may be used as a primary supportive nutritional aid to help manage inflammation or in conjunction with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids.

Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Buffered Aspirin: Buffered aspirin is an excellent anti-inflammatory and painkiller in dogs (Do NOT give your cat aspirin unless prescribed by your veterinarian.). It can be used along with glucosamine/chondroitin products. With all aspirin products used in dogs, there is a risk of intestinal upset or in rare cases, gastric ulceration. Because of these problems, it is recommended that if a dog develops signs of GI upset, the product be discontinued until a veterinary exam can be performed. (By giving aspirin with a meal, you may be able to reduce the possibility of side effects.) Using buffered aspirin formulated just for dogs makes dosage and administration much easier.

Carprofen (Rimadyl), Etodolac (EtoGesic), Deracoxib (Deramaxx), Ketoprofen, Meloxicam: These are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) developed for use in dogs with osteoarthritis. They are strong and effective painkillers and anti-inflammatory agents. They are prescription products and because of potential side effects, careful adherence to dosing quantity and frequency must be followed. The manufacturers recommend periodic bloodwork to be done on animals that are on this product to monitor any developing liver or other problems resulting from their use. These products are often used initially with glucosamine therapy and then as the glucosamine product begins to work, the NSAID dose may be reduced or even eliminated. Any NSAID should not be used with aspirin, corticosteroids, or other NSAIDs. Acetaminophen (Tylenol), and ibuprofen have many more potential side effects and are not recommended without veterinary guidance.

Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids have been used for many years to treat the pain and inflammation associated with osteoarthritis, however, their use is controversial. Corticosteroids act as a potent anti-inflammatory, but unfortunately, have many undesirable short- and long-term side effects. Because of these side effects and the advent of newer, more specific drugs, corticosteroids are generally only used in older animals with flare-ups where all other pain control products have failed. Corticosteroids are a prescription product and come in both a pill and injectable form.

How do we prevent hip dysplasia?

When it comes to preventing the formation of hip dysplasia, there is only one thing that all researchers agree on, and that is selective breeding is crucial.

There are many different theories on how to prevent the progression of hip dysplasia. As discussed earlier, nutrition, exercise, and body weight may all contribute to the severity of degenerative joint disease after the hip dysplasia has developed. When it comes to preventing the formation of hip dysplasia, there is only one thing that all researchers agree on, and that is selective breeding is crucial. There will be a lot of new information coming forward in the future concerning other factors that contribute to hip dysplasia, but for right now, we have to stick to what we know for sure. We know that through selectively breeding animals with good hips, we can significantly reduce the incidence of hip dysplasia. We also know that we can increase the incidence of hip dysplasia if we choose to use dysplastic animals for breeding. Breeding two animals with excellent hips does not guarantee that all of the offspring will be free of hip dysplasia, but there will be a much lower incidence than if we breed two animals with fair or poor hips. If we only bred animals with excellent hips it would not take long to make hip dysplasia a rare occurrence. If owners insisted on only purchasing an animal that had parents and grandparents with certified good or excellent hips, or if breeders only bred these excellent animals, then the majority of the problems would be eliminated. For the best results, buyers should look at three or four generations of dogs prior to theirs to ensure that there are no carriers in the bloodline. Following the newer recommendations for exercise and nutrition may help, but will never come close to controlling or eliminating the disease if stricter requirements for certified hips are not instituted or demanded.

Summary

Hip Dysplasia is a widespread condition that primarily affects large and giant breeds of dogs. There is a strong genetic link between parents that have hip dysplasia and the incidence in their offspring. There are probably other factors too that contribute toward the severity of the disease.

Osteoarthritis is the result of degeneration of the joint due to hip dysplasia. Surgical and medical treatments are targeted to prevent and treat the resulting osteoarthritis. The best way to prevent hip dysplasia is through selection of offspring whose parents and grandparents have been certified to have excellent hip conformation.

References

Cook. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Canine Hip Dysplasia. Compendium. August 1996.

Francis, David; Millis, Darryl L. Managing the Arthritic Patient. DVM News Magazine. October 2001.

Johnston, Spencer A; Budsberg, Steven C. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Corticosteroids for the Management of Canine Osteoarthritis. Veterinary Clinics. Small Animal Practice. July 1997.

Kapatkin, Amy S; Mayhew, Philipp D; Smith, Gail K. Canine Hip Dysplasia: Evidence-Based Treatment. Compendium. August 2002.

Kealy. Five-year limited study on limited food consumption and development of osteoarthritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. January 15, 1997.

Mclaughlin, Ronald M; Roush, James K. Symposium on Medical Therapy for Patients With Osteoarthritis. Veterinary Medicine. February 2002.

Mclaughlin, Ronald M; Roush, James K. Symposium on Alternative and Future Treatment Modalities for Osteoarthritis. Veterinary Medicine. February 2002.

McNamara, Paul S; Johnston, Spencer A; Todhunter, Rory J. Slow-Acting Disease-Modifying Osteoarthritis Agents. Veterinary Clinics. Small Animal Practice. July 1997.

Montgomery. Canine Hip Dysplasia. Compendium. July 1998.

Tomlinson. Symposium on Canine Hip Dysplasia. Veterinary Medicine. January 1996.