Heart Disease

New Hope for Heart Disease

Submitted by HRC member Madeline Erickson

"Sinead," a 2 1/2-year-old black-and-white Border Collie mix, is jumping on the loveseat using the living room coffee table as a springboard. In many houses, this dog would be in trouble for furniture surfing, but owner Marjorie Smith pushes back the tears and says, "That's my girl."

"Sinead," a 2 1/2-year-old black-and-white Border Collie mix, is jumping on the loveseat using the living room coffee table as a springboard. In many houses, this dog would be in trouble for furniture surfing, but owner Marjorie Smith pushes back the tears and says, "That's my girl."

When she was 15 months old, Sinead was diagnosed with a congenital heart condition known as pulmonic valve stenosis (PVS). The Border Collie had made her way to the Project Hope Animal Shelter in Metropolis, Ill., with a persistent cough and blood in her urine and stool. Smith, the executive director of the shelter, took the dog to a veterinarian who discovered a heart murmur indicative of PVS.

The condition occurs when a malformed pulmonary valve causes a partial obstruction of normal blood flow. Consequently, the heart must work harder to pump blood to the lungs, which over time can lead to heart failure. Pulmonic stenosis occurs most commonly in small- to medium-sized dogs including Beagles, Wire Fox Terriers, Chihuahuas, Miniature Schnauzers, Samoyeds, Cocker Spaniels, Bulldogs, and Scottish Terriers.

Within weeks of moving to the Smith house, the blood had disappeared from Sinead's urine and stool. Living in a more controlled environment where Sinead's activity and stress levels could be limited seemed to help. However, within two months, Sinead was having fainting episodes, known as syncope, caused by inadequate blood flow to her brain.

Veterinarians at the University Of Missouri College Of Veterinary Medicine performed a balloon valvuloplasty to dilate Sinead's pulmonic valve. "In this procedure, a catheter is inserted into the jugular vein in the neck. Using a fluoroscope, an X-ray machine that stores digital video on a computer, the catheter is guided to place a balloon into the pulmonic valve," says Deborah Fine, D.V.M., M.S., assistant professor in small animal cardiology.

"The balloon is then inflated to dilate the narrowed opening," Fine continues. "The size of the balloon varies based on the size of the animal and the severity of obstruction." The balloon valvuloplasty plus post-procedural care costs approximately $1,500, and the initial workup to establish the diagnosis and determine any other abnormalities runs from $300 to $500. Costs may vary depending on the case and veterinary clinic.

Traditionally, the only treatment for Sinead's PVS would have been an open-chest procedure in which doctors surgically remove or loosen the fusion in the affected valve. In the early 1980s, the first nonsurgical treatment of PVS was performed. Today balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty is the procedure of choice for relief of nearly all cases of PVS.

Advances in Cardiac Treatments

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, one in 10 dogs in the United States suffers from heart disease. Although some heart disease may be mild enough to go unnoticed for years, other cardiac problems can result in suffering or sudden death for dogs. Today advances in veterinary medicine and research are giving hope to owners and breeders. New treatments and procedures have made the life expectancy for dogs with heart disease better than ever. Cutting-edge research might also one day lead to genetic tests for some kinds of heart disease that would enable breeders to potentially eliminate disease in their bloodlines.

Dennis Burkett, V.M.D., Ph.D., a consultant in cardiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, says minimally invasive surgery is preferable in most canine surgical heart approaches. The less invasive the procedure, the less traumatic it is to the dog's body, and the quicker the recovery time. "The future is to continue to develop these minimally invasive procedures to correct cardiac and cardiovascular congenital diseases," Burkett says.

An example is the procedure used to correct a common congenital defect known as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Breeds commonly at risk for this defect are Maltese, Pomeranian, Shetland Sheepdog, and Kerry Blue Terrier.

"PDA occurs when the ductus arteriosus — a vessel in fetuses that allows blood to bypass the as-yet undeveloped lungs — remains open after birth," Burkett explains. "The result is a leak from the aorta, the major blood vessel supplying blood to the body, through the open ductus into the pulmonary artery supplying blood to the lungs and then back again to the left ventricle, causing the left ventricle to work harder to maintain normal blood flow. Changes may occur in blood pressure, and the heart may enlarge as it tries to make up for the abnormal blood flow, ultimately leading to heart failure in most cases."

As with PVS, the traditional treatment for PDA was open-chest surgery. An alternative procedure using coils, or small pieces of metallic material imbedded with Dacron, was developed in dogs after being first described in humans in 1992. The Dacron fibers allow formation of a clot that eliminates blood flow through the PDA.

In describing the procedure, Burkett says, "A veterinarian does a small cut down over a vessel, usually in the leg, and passes a catheter into the femoral artery. Through the catheter a veterinarian can strategically place the coils within the ductus." Although no statistics are available, Burkett estimates 90 percent of surgeries are successful when performed by a skilled cardiologist. The average cost for the procedure ranges from $2,500 to $3,500, although costs could vary.

A Pacemaker for Dogs

Although not as new a procedure as the PDA coil occlusion, surgical insertion of a pacemaker can be a panacea for a dog suffering from slow heartbeats. "It's like changing the batteries on an old toy," says Fine of the University of Missouri. "The dogs have all this pep and can do things that they haven't done in a long time." If a dog is a suitable candidate for a pacemaker — meaning that the dog does not have some other disease present from which he will likely die soon — then a pacemaker is a 100 percent cure.

Most dogs in need of a pacemaker experience fainting episodes or cannot tolerate prolonged exercise. The cause of the fainting and weakness is a slow heart rhythm, usually described as a third-degree, or complete, atrioventricular (AV) block. An AV block means that the heart's electrical signal is not passing properly from the atrium to the ventricles. When the ventricles do not receive electrical impulses, they generate impulses on their own called ventricular escape beats. These natural backup signals are slow and cannot produce the signals needed to maintain full functioning of the heart muscle. The result is inadequate pumping of blood to the body and the brain. A pacemaker is required to directly stimulate the ventricle to "pace" at a higher rate.

"The pacemaker insertion requires general anesthesia and fluoroscopic guidance of a lead into the right side of the heart," Fine says. "The lead is guided into the jugular vein through a small incision in the neck. A silicone-coated grappling hook end attaches to heart muscle to keep it in place until scarring occurs. The pulse generator is permanently implanted underneath the skin in the underside of the neck." The cost for a pacemaker and postoperative care is approximately $2,000, plus the presurgical workup to rule out other diseases is about $500. Costs could vary.

Following surgery owners must use a harness rather than a neck collar for leash walks, but within a few days of the procedure dogs and owners barely remember that heart problems existed. Dogs must always wear a harness or gentle leader type device to prevent pressure on the pacemaker lead.

Dealing with DCM

Although some canine heart problems appear later in life, many such as Sinead's PVS are congenital, or present at birth. Many more are in fact hereditary. "Breeders face difficult decisions in choosing which dogs to breed," says Kathryn M. Meurs, D.V.M., Ph.D., the Richard L. Ott Professor of Small Animal Medicine and Research at Washington State University School of Veterinary Medicine. "It is frustrating for breeders as they strive to perpetuate the best qualities of their dogs while at the same time avoid passing along the potential for a heart condition."

Meurs has spent much of her career studying hereditary heart conditions in dogs and cats. One such condition is dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a disease of the heart muscle that results in weakened contractions and poor pumping ability. "As the disease progresses, the heart chambers become enlarged," she explains. "One or more valves may leak, and congestive heart failure may develop. A diagnosis of DCM is often unexpected for breeders. With many inherited heart conditions, physical symptoms don't manifest until very late in the disease. Sudden death may be the first sign that there was a condition."

DCM is commonly observed in Great Danes and Doberman Pinschers. Other affected breeds are Irish Wolfhounds and Boxers, which experience arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC).

Aortic stenosis (AS) and subaortic stenosis (SAS), similar to PVS in many ways, are characterized by extra tissue that forms a ridge inside or below the aortic valve causing an obstruction that makes the heart work harder to pump blood. Golden Retrievers and Newfoundlands are commonly affected by these conditions.

Though the genetic basis of DCM, AS and SAS is uncertain, Meurs hopes to identify the gene mutations that causes these defects. Determining the responsible genes will help to identify the diseases before dogs show clinical signs. This would allow development of screening tests to identify carrier and affected dogs so they may be removed from breeding programs.

Meanwhile, Mark Oyama, D.V.M., DACVIM, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, also is working to learn more about the genetics of DCM in Boxers, Doberman Pinschers and Great Danes. He is using a new microarray analysis technology that assesses more then 23,000 genes. Before the new technology, gene analysis was done one gene at a time, making it time-consuming and tedious.

Oyama's team discovered 478 genes that operated much differently than those of healthy dogs. From this pool, they identified 167 genes that might play a role in the development and progression of DCM. Ultimately, the microarray study could provide clues about which genes are responsible for the disease and lead to the development of blood tests for early detection and possible new treatments for DCM.

Whether dealing with cutting-edge surgical procedures or genetic research, it is obvious that the veterinary medical community has more to learn about canine heart disease. However, as Marjorie Smith, the owner of the Border Collie with PVS, says, "Sinead is proof that we have made so many advances in veterinary cardiac medicine."

Differences Between the Canine and Human Heart

A dog's heart beats between 70 and 120 times a minute, compared to the human heart, which beats between 70 to 80 times a minute.

Dogs seldom experience heart attacks or strokes. In humans, a heart attack occurs when the coronary arteries become narrowed or blocked, usually with hardened plaque, or fat. This can interrupt blood flow to the myocardium resulting in an infarction, or lack of blood supply. Dogs most likely do not often have myocardial infarctions because of differences in their metabolic programming. Strokes in humans occur when blood clots choke the blood supply to a part of the brain. When a stroke occurs in a dog, it is usually in an animal that is very old.

In large-breed dogs, the most common type of heart disease is dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a condition that humans also can develop. Doberman Pinschers, Boxers and Great Danes appear to be especially prone to this disease. Sudden death due to ventricular arrhythmia is not uncommon. Humans also experience arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), which is similar to arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in Boxers.

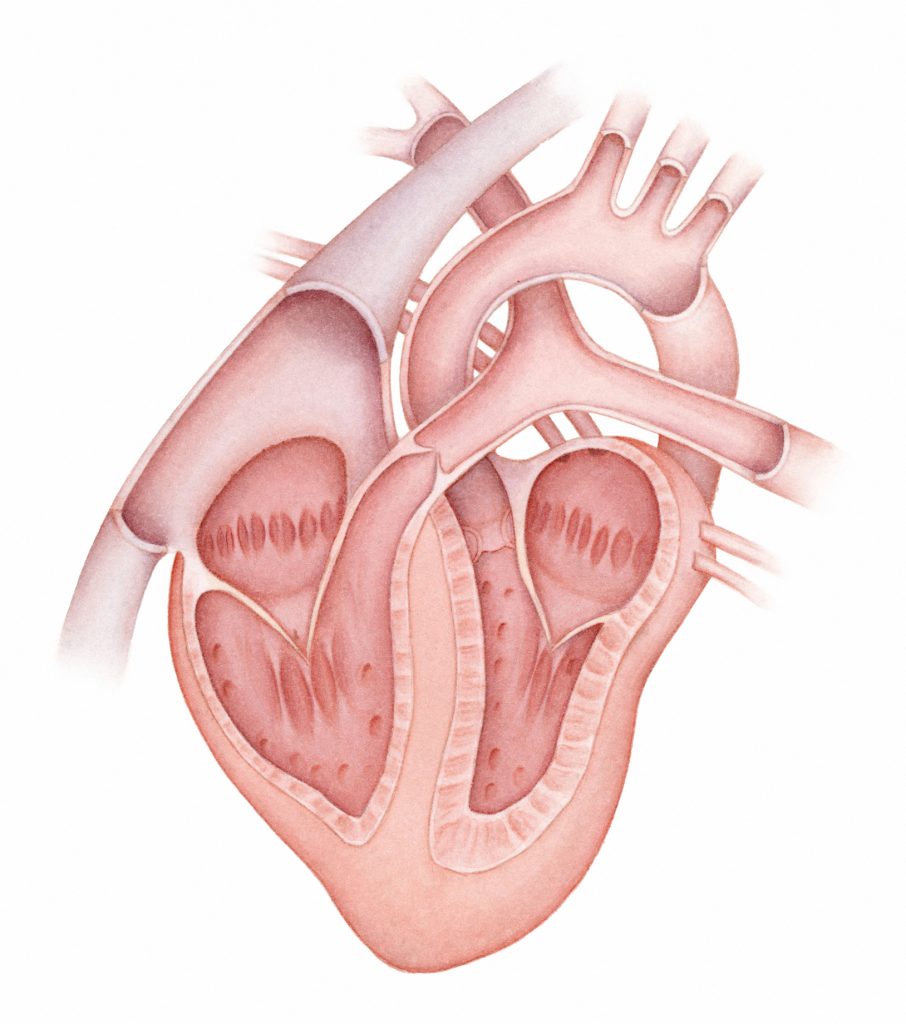

How the Canine Heart Works

The canine heart is much like a human heart. Made up of four chambers, the heart's upper half consists of the right and left atria, while the lower portion contains the right and left ventricles. For blood to flow correctly, the left atrium must contract to push blood into the left ventricle. The left ventricle then contracts to push blood out to the body, while the right ventricle pushes blood out to the lungs. If the ventricle contracts, or beats, out of rhythm, it doesn't pump blood effectively, and the brain and body don't receive an adequate supply of oxygen.

Valves, located between the atrium and ventricle on each side of the heart, regulate the flow of blood to help the heart work efficiently. The movement of blood results from electrical impulses transmitted throughout the heart. The impulses not only direct the heart to beat in the first place, but also enable the heart to maintain a steady, regular rhythm.

With each heartbeat, an electrical impulse from the sinoatrial (SA) node of the right atrium causes the muscles of the atrium to contract to pump blood. The electrical signal is then carried through the atrioventricular (AV) node into the ventricles, causing them to contract. The SA node is the body's natural pacemaker since it controls heartbeats. The strong heartbeats generated by these regular electrical impulses create the rhythm and force necessary to pump blood throughout the body.

Used with permission from Today's Breeder, Nestle Purina PetCare

Barb Fawver, Editor

Today's Breeder - Nestle Purina PetCare

St. Louis, MO

314-982-2267